Outline: 022-E4.2-Order in Worship-Eucharist

Passage: 1 Corinthians 11:17-34

Discussion Audio (1h09m)

Actions and attitudes in the Christian church that abuse the poor

is the same as abusing Christ

The English Standard Version Study Bible notes gives the heading for this section of 1 Corinthians as “Social snobbery at the Lord’s Table.” Reading Corinthians from Reading the New Testament commentary series gives it the subheading “Social Significance of the Supper.” In other words, theology has direct bearing on social relationships. What, then, is Paul’s theology in this passage?

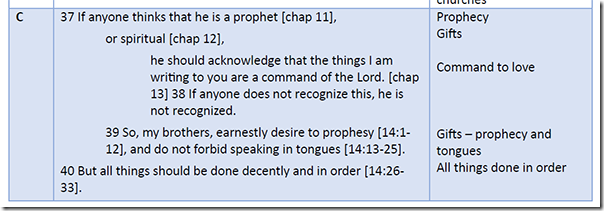

The passage is broken into three major sections:

- The problem statement (vv.17-22)

- Theology (vv.23-26)

- Observations and solutions (vv.27-34)

The Problem

The Corinthian letter to Paul did not mention this problem. It is entirely possible that those in leadership did not even recognize it to be a problem. Or, they were too embarrassed to bring it up to Paul. Whatever the case, Paul heard about it, quite possibly from the servants and/or slaves of the house in which the Corinthian church met.

The best reconstruction of the problem appears to be that it happened during the meals held at the Corinthian assembly (gathering, church) at which time the Last Supper of Jesus was remembered. The church consisted of members from all social strata – from nobility and the wealthy to the slaves and the poor. It appears that the church was following Roman customs in its meals; i.e., those with leisure time – the wealthy – arrived early and had access to the triclenium and the best foods and drinks offered there, while the less well-to-do arrived later, hungry, and had to make-do with what was left and had to settle for seating or standing outside in the atrium area. Instead of united fellowship the meal was an event in which social divisions were heightened in visibility.

Paul offers no commendation (praise) for allowing this divisive cultural tradition/norm to exist at a church function. The Corinthians may be repeating words from the Last Supper, but because of their present actions, Paul writes that this is not “the Lord’s Supper” but “their own supper.” Instead of fostering community and communal good, the meal is dividing and highlighting the harmful aspects of individualism.

Theology

Paul writes that “remembrance” is not merely recollection about Jesus and the events of the Last Supper, but for it to be truly remembrance the church must participate actively in what the supper means.

Paul writes that the supper is an activity in which social divisions and hierarchies of authority are erased. It is a remembrance of the act of love of Jesus that led to his death on the cross. It is a remembrance of the birth of a new community, based not on nationality, race, gender, or social status, but on adoption into God’s family as a friend and brother of Jesus.

The manner in which the Corinthian church “remembered” the Last Supper was a travesty of what it was supposed to teach. The Lord’s Supper was supposed to be a proclamation of the gospel of restoration of relationships from hierarchy and roles to egalitarianism, but the Corinthians had made it the exact opposite of that.

Observations and Solutions

Paul writes that the church must examine herself before partaking of the Lord’s Supper to see if she is worthy. This section, in particular, has been lifted out of context by much of traditional Christian interpretations. It has been made to say that individual Christians must examine themselves to determine if there is any sin that might cause them to be unworthy of partaking of the Supper, and that if done unworthily, they will incur judgment from God.

That is not what Paul intended. The entire context is in the framework of social justice. The Corinthian church, as a whole, was allowing and even promoting social divisions and inequality through her actions. Paul is writing against this “sin.” It is a sin committed by the entire church, not specifically individuals. Paul is calling on the church to examine herself.

In the context of this letter and in the light of the discussion he has offered the Corinthians up to this point, one should see that, for Paul, to eat the bread and to drink the cup of the Lord in an unworthy way is eating and drinking with an attitude of self- centeredness, of individualism or arrogance.[1]

This is not a call for deep personal introspection to determine whether one is worthy of the Table… [It is] a call to truly Christian behavior at the Table. It is in this sense that the Corinthians are urged to examine themselves. Their behavior has belied the gospel they claim to embrace. Before they participate in the meal, they should examine themselves in terms of their attitudes toward the body, how they are treating others, since the meal itself is a place of proclaiming the gospel.[2]

When the church allows traditional and cultural social divisions into her life, she becomes unworthy and guilty of abusing Christ himself.

Such an abuse of the "body" is an abuse of Christ himself. The bread represents his crucified body, which, along with his poured out blood, effected the death that ratified the New Covenant. By their abuse of one another, they were also abusing the One through whose death and resurrection they had been brought to life and formed into this new eschatological fellowship, his body the church.[3]

Paul perceives that all is not well with the church and places fault on how the church is treating the poor. He attributes this to “judgment from the Lord.” But that should not be read as God causing or punishing, but as allowing consequences of their poor behavior to bear its fruits. It is also vital to note that Paul never writes that individuals will be the direct recipient of judgment but rather the church.

The solutions Paul proposes are twofold. First – his recommended solution – is that the church correct her abuses and welcome everyone to the Table so that she will become a worthy participant in the Lord’s Supper. The second suggestion that Paul makes is that if there are groups or factions that cannot accept the theological significance of the Lord’s Supper and want to continue traditional Roman banquets that they do so in their own homes before coming to meet with the rest of the church. That way judgment will not fall upon the church.

Throughout this passage Paul never directly attacks social and cultural customs. He never commands the wealthy to share with the poor. He never writes that social inequities are wrong. But what he does by introducing a theology of equality and egalitarianism is to quietly chip away at the foundations of human priorities of wealth and privilege, and the status and security those things can afford. What Paul does write is that within the church assembly, such things must not become sources of division and factions. When the church gathers, no individual or group must be allowed to feel shame and dishonor because of what they don’t have or who they are not.

As noted throughout, this paragraph has had an unfortunate history of understanding in the church. The very Table that is God's reminder, and therefore his repeated gift, of grace, the Table where we affirm again who and whose we are, has been allowed to become a table of condemnation for the very people who most truly need the assurance of acceptance that this table affords—the sinful, the weak, the weary. One does not have to "get rid of the sin in one's life" in order to partake. Here by faith one may once again receive the assurance that "Christ receiveth sinners."

On the other hand, any magical view of the sacrament that allows the unrepentant to partake without "discerning the body" makes the offer of grace a place of judgment. Grace "received" that is not recognized as such is not grace at all; and grace "received" that does not recognize the need to be gracious to others is to miss the point of the Table altogether.[4]

[1] Understanding the Bible Commentary: 1 Corinthians, entry for 1 Cor. 11:27.

[2] New International Commentary on the New Testament: The First Epistle, entry for 1 Cor. 11:28.

[3] NICNT, introduction entry on 1 Cor. 11:17-34 (D. Abuse of the Lord’s Supper).

[4] NICNT, entry for 1 Cor. 11:31-32.